John Proctor Is the Villain

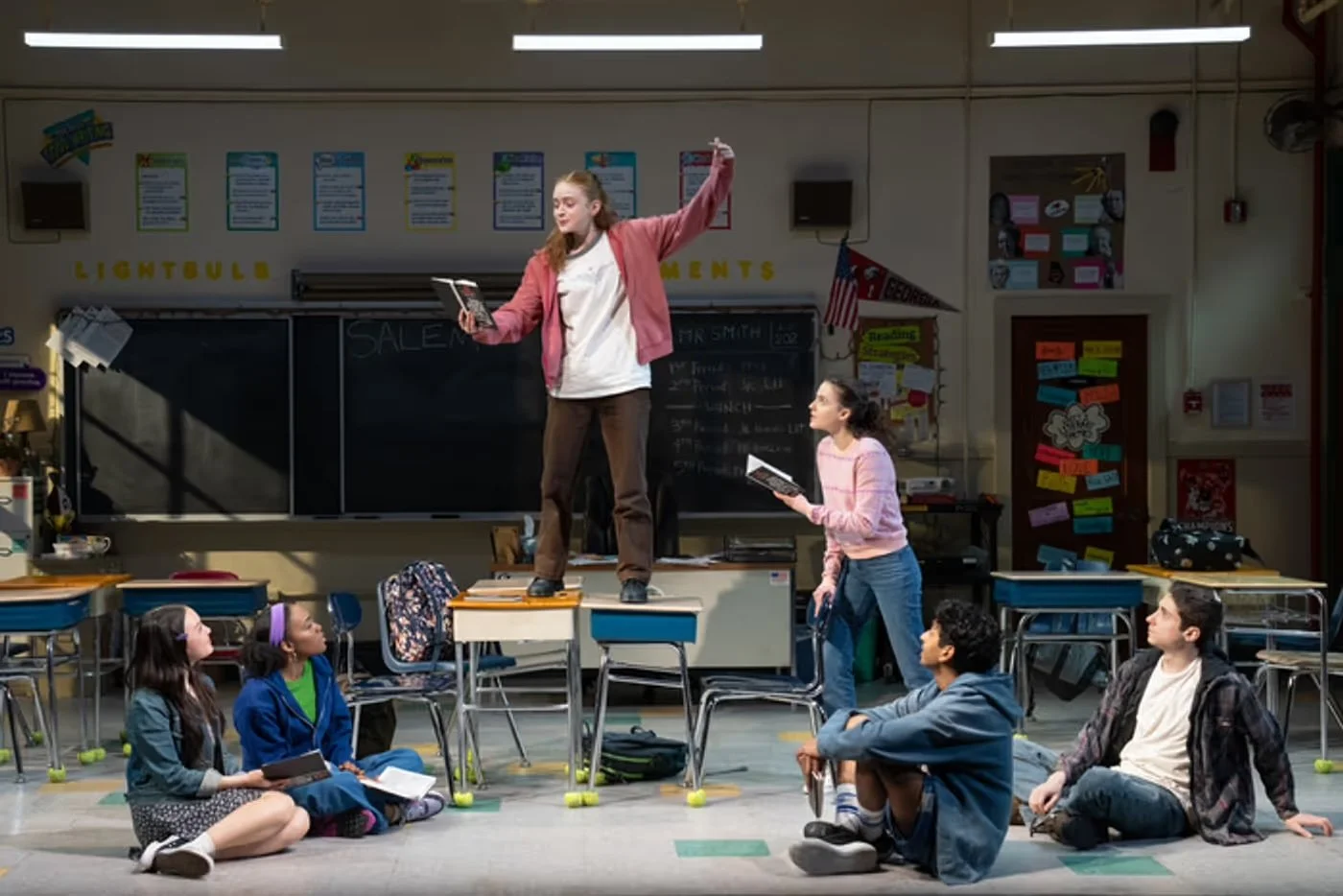

Amalia Yoo, Morgan Scott, Sadie Sink, Fina Strazza, Nihar Duvvuri and Hagan Oliveras

Photo by Julieta Cervantes

One could be forgiven for thinking John Proctor Is the Villain is a two or three-hour long production. Once Kimberly Belflower’s vital, gripping play comes to an end, it wouldn’t be surprising for audience members to be exhausted after traversing this political and emotional journey. But the play clocks in at one hour and 40 minutes. It doesn’t even have an intermission — but it moves at a breakneck pace, thanks to the rapid-fire direction by Danya Taymor, unflinchingly tackling some of the heaviest, most exhausting subjects in contemporary culture.

It’s 2018 in a rural Georgia town, and a junior year English class is embarking on two rites of passage: sitting through a mortifying and uninformative sex-ed class and studying The Crucible. Both are led by Carter Smith (Gabriel Ebert), a teacher beloved for both his cheerful disposition and appearance in sweatpants and who informs the class unilaterally that The Crucible is “a great play about a great hero.”

This statement goes unchallenged at first — not surprising, given that the girls’ request to form a feminism club is declined due to it being “a tricky situation,” until Mr. Smith offers to sponsor it. Nonetheless, the girls are urged to “choose [their] words with care” because “feminism is just — people are sensitive right now,” according to the school counselor Miss Gallagher (Molly Griggs).

It’s very satisfying when the mild-mannered Beth (Fina Strazza) responds to these platitudes with, “It is literally your job to facilitate situations like this! Just do your job!” (She does apologize immediately afterward.) Beth is joined by the wealthy Ivy (Maggie Kuntz); Nell (Morgan Scott), recently relocated from Atlanta; and Raelynn (Amalia Yoo), who is reeling from recent breakups with both her boyfriend Lee (Hagan Oliveras) and best friend Shelby (Sadie Sink).

One year has passed since #MeToo gained notoriety, and the effects of the movement are rippling through this conservative town. What is easy to support in theory becomes complicated and personal when Ivy’s father is accused of inappropriate conduct with an employee and her instincts to side with her family clash with her political and social convictions. Allegiances are further tested when Shelby returns to town after a mysterious, months-long absence. Her mere entrance onstage, a torpedo of bravado and emotion, makes it clear her return will inspire chaos, and the ripple effects will go far.

Morgan Scott, Maggie Kuntz, Fina Strazza, Amalia Yoo, Gabriel Ebert and Molly Griggs

Photo by Julieta Cervantes

Just as The Crucible served as an allegory for the Red Scare and McCarthyism, Belflower’s play does the same for the lives of the students, paralleling those in the play. As their perceptions of their surroundings and the men in them change, so do their perceptions of Miller’s characters. It is Shelby who voices the statement when, rather than read Proctor’s final speech with admiration, she dismisses his desperation to protect his name as false.

“Your name is literally just a word that someone else gave to you … That’s what names are: They’re fiction. But my body is a fact. I live inside of it … Abigail was a human being … but John Proctor is just obsessed with this made-up thing … He’s just pretending, like, I dunno, like, his fiction is more important than her fact? I mean, that sucks. Like, John Proctor is clearly the villain, right?”

Belflower’s script is remarkable, not only due to its relevance but how accurately she captures the vernacular of teenage conversation. Conversations about intersectionality and allyship are peppered with numerous “like” and “I dunno. The lack of formality does not dim the dialogue’s impact, which paints a stark portrait of just how much these young women are forced to shoulder every day.

These portraits are drawn in stark contrast to their male counterparts, played by Oliveras and, in a standout comedic turn, Nihar Duvvuri as a boy who is forced to join the feminist club to gain badly-needed extra credit. These are young women whose conversations include thoughtful discourse about how “white feminism is monopolizing the mainstream body positivity movement,” but what was a “kiss rape” — a forced kiss against her will — to Raelynn is merely a “conversation” to Oliveras.

Belflower’s writing is only made better by the cast, each member delivering outstanding performances. While Sink is undoubtedly the most well-known of the cast, she is equally a member of an ensemble working in powerful harmony. Strazza gracefully depicts Beth’s nervous timidity, showing how close to snapping this overachiever really is. Kuntz brings depth to Ivy’s opposing loyalties, and Scott’s easy confidence as Nell is admirable. Yoo’s portrayal of Raelynn’s conflicts is complex and believable, as is her chemistry with Sink, depicting the intense intimacy of teenage female friendships.

Out of all the girls, Sink is probably given the least to say but the most to communicate. As a teenager wrestling with trauma and anger she has no idea how to articulate and masking it with casual bravado, Sink practically vibrates with emotion. The raise of an eyebrow or the suppression of a smile, as she masks her body with Sarah Laux’s oversized costumes, communicates so much, but she still leaves much to the viewer’s imagination.

As the dubious figures of authority, Griggs and Ebert both excel. Ebert’s easy affability inspires adoration and teases just enough of a darker side, while Griggs inspires sympathy for her character’s anxious timidity and excitement for her growth by the play’s end.

I want to lament that the ending comes too soon, but Bellflower’s play knows when it should stop. Its vitality as it moves full-throttle through these teenagers’ chaotic lives, needs to remain brief to contain the enormity of its impact. And it definitely does. John Proctor’s name may not have meant much to Shelby, but to a feminist theatergoer eager to watch the patriarchy be challenged, Kimberly Belflower’s means a great deal to me.